Jane McConnell on Alterations and Adjustments

Alterations and Adjustments: A Fragmented Rendition of the Female

By Jane McConnell

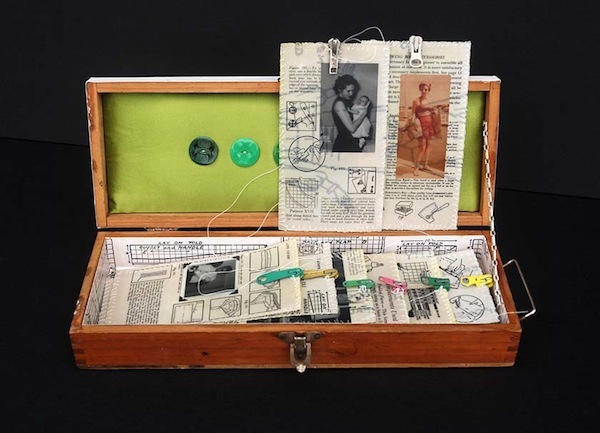

An artist's book is a source of information meant to engage its reader in a textual and palpable way. Its purpose is, as the title of scholar Lynn S. Vieth's article declares, to become a medium of information that “challenges academic convention” through the means of (as she later suggests) “'hands-on' knowledge” (14). Julie Shaw Lutts's artist's book Alterations and Adjustments performs this task thoroughly. Only one copy of this book exists, which is structured to look like a sewing kit from 1940 to 1950 (Russell). Its cover is a wooden sewing box and its end pages are its interior. The text block itself consists of 20 unattached, hand-sewn pages. The content of the artist's book is largely interpretive, forcing its reader to dig deeper into Alterations's material body to discern its internal story. Still, its creator's overlying purpose remains largely distinct. In Alterations, Lutts disrupts a continually relevant depiction of the conventional woman. She enforces this distortion through the use of a sewing kit as the content's medium, the interactive design of the book, and the duality of the pages.

Lutts's most obvious creative move in composing Alterations was choosing to make it a sewing kit, a possession that exudes stereotypical femininity. This decision initially establishes the stereotyped image of a woman. The reader immediately relates Alterations to the female gender from merely looking at the cover; they have already started manipulating the book's content to fit this impression.

The reader cannot be faulted for the judgment—it is the history women have with sewing that creates such prejudice. In essay “The Needle as the Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power,” the authors emphasize that “needlework has been understood to be overtly feminine for some time in American culture. Therefore it is unsurprising that the act of needlework itself has been as such a valuable part of female gendering through our history” (Pristash, Schaechterle, and Wood 17). In fact, the authors even later describe that learning and creating needlework was a coming-of-age process both social and practical in nature. Even during World War II, a period of time when women (out of necessity) began taking up work outside of their domestic responsibilities, many of those women continued to sew; they believed that it was still a required duty (McLean 72). Alterations considers this relationship between a woman and her sewing kit. It was, essentially, a woman's toolbox—her means of providing. It was considered a representative of her entire role. Yet Alterations reminds the reader that the idea of a woman's sewing kit and the physical contents within it form the paradoxical concept of a simultaneously personal and communal relationship between a woman, her sewing kit, and her society.

The theme of communal relationship corresponds to the reader's experience of being both spectator and participant in their examination of the artist's book. By opening Alterations, the reader now sees the book's content through the eyes of its protagonist and becomes subject to her narrative. At the same time, the reader is not the protagonist. The reader develops a voyeuristic view of the book that, while a common experience of any audience, becomes jumbled by the degree to which the reader is involved in the woman's story.

To enhance the reader's complicated experience as protagonist and voyeur, Lutts furthers the interaction by giving the reader an array of individual pages, each with its own zipper and thread-bound border. The lack of a material binding for the text block emulates the reality of a woman's sewing kit: a house for leftovers, the unused or damaged pieces of cloth. The reader's initial reaction as he or she pulls the pieces and spreads them out to dissect is to fasten them together in some way. This impulse to order the pages, to organize and control the information, follows an inherent and traditional appeal that aligns with the conquest-like, overpowering masculine world that surrounded women in the 40's and 50's (and still persists globally to this day). The reader discovers, with effort, that the pages do fit together visually, forming a diagram labeled “Pattern for Success.” Once the reader successfully orders and catalogs the pages, they synchronously adopt the conventional male role of domineering over the female and the conventional female role of conforming to his controlling methods.

Lutts conflicts the reader by offering the opportunity to take on the role of a man invading the female space of the wooden box or the role of the woman that suffers the assault. By doing so, she dislocates the linear separation between the male and female gender. The reader attempts to reconcile this confusion by allowing the vision of the female figures in the diagram to remain fragmented by the unwilling cohesion of the page borders to one another but ultimately forcing “Pattern for Success” to maintain its ideal shape. Along with this study of the content as a whole, Lutts provides a deeper consideration of the disproportionality of female construction in Alterations on the other side of the text.

The diagram, though a large focus of the artist's book, is not its only text; the backs of the pages in “Pattern” expose an entirely different skein of information. On the one hand, the diagram reveals that there is a whole to the pieces, thus a continual plot. Each piece of the diagram depends on its companion pages. On the other hand, each opposing face of the diagram page writes its own essay, with its own specific subtopic. Suddenly, the major plot line discovered on the one side fractures into different narratives.

On this heterogeneous side of Alterations, the reader discovers the woman in varying scenes of her life. They see her as a child and a mother. They see her in her social environment. They see her sewing even from a young age and, alternatively, framed by illustrations of boating knots—a typically masculine counterpart to sewing knots. The individual pages represent a new memoir, but the entire collection houses only one distinct through line: the observation that Alterations presents the woman in various social and biographical contexts. Each photograph reflects a woman in different stages of her life. The collection, however, does not progress through a linear timeline.

Without using methods of organization such as incorporating a timeline or even physically sewing the pages together, Alterations once again confuses the reader and forces them to reconsider Lutt's expression of a woman in the book's cover. The pages insinuate a win-lose type of reading. Although the universal woman is initially portrayed through a single item (the sewing kit), she then becomes a fragmented display simultaneously of several parts making a whole. She also includes several parts working independent from one another. The reader must choose between rationalizing the fragments through the diagram or allowing a more liberal classification through deeper consideration of the essays on the other side, at the cost of the main plot discerned in the diagram.

It is, ultimately, a choice. In Alterations, Lutts introduces the complex reality of society's depiction of a woman—she may be viewed and characterized through the traditional symbol of a sewing kit, or she may be viewed as a woman with her own personalized motifs. Her opinions and role may be the same as all other women, or she may be of free mind, separate from those that surround her. The reality of the situation is that people are given the choice to perceive her as either of these roles, so she is at once both a stereotyped character and a single, specialized entity. There will always be argument over the identity of a woman. There will always be that disconcerting clash of contrasting definitions that Lutts so clearly represents in her artist's book—and with it, a call for consideration, interpretation, and forming one's own hypothesis on the true essence of a conventional woman. Lutts forces her readers into this important experience.

Works Cited

Lutts, Julie Shaw. Alterations and Adjustments. 2004. Print.

McLean, Marcia. “'I Dearly Loved that Machine': Women and the Objects of Home Sewing in the 1940s.” Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles: 1750 – 1950. Eds. Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010. 69-89. Print.

Pristash, Heather, Inez Schaechterle, and Sue Carter Wood. “The Needle as the Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power.” Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles: 1750 – 1950. Eds. Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2010. 14-29. Print.

Russell, Laura, ed. "Uncommon Threads Artist Roster." 23 Sandy Gallery Portland Oregon. 23 Sandy Gallery, n.d. Web. 26 Mar. 2013. <http://gallery.23sandy.com/uncommon-threads/shawlutts/>.

Vieth, Lynne S. “The Artist's Book Challenges Academic Convention.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 25.1 (2006): 14-19. Web.